Adam Tranter is the Bicycle Mayor for Coventry, co-host of Streets Ahead podcast and CEO of communications agency, Fusion Media.

The Midlands has a long-standing history with transport and industry. An economy which once thrived on making things to help people move, now needs to take tried-and-tested tactics from other global economies; some of which have embraced some great Midlands exports, but shunned others.

While the Midlands is famous for its car manufacturing, many forget that the region was originally the global centre of bicycle manufacturing, with many car brands originally starting on two wheels. The bicycle had an incredible impact on the Midlands, and the world, and still remains the most efficient form of transportation man has ever known, bar none.

Interestingly, the first real advocates for widespread motoring were cyclists; Midlands-based Henry Sturmey – famously known for his work on the three-speed hub for bicycles, edited both Cyclist and Autocar magazines in the mid-1890s and, with peers, was instrumental in getting better roads for both cyclists and automobiles.

In a narrative of apparent tribalism between motorists and cyclists, it would be hard to imagine this dual occupation in today’s world. But really, transport should be a case of using the best tool for the job, and people shouldn’t be defined by their transport choices. Many of our Midlands towns and cities are a mirror image of the industry and employment they house; many having become completely overrun with the private motor vehicle, a hangover of the most popular and lucrative part of our manufacturing past.

But if we’re really using the best tool for the job, it’s clear that cycling has to be enabled as an option. It has to be a real option for the 68% of all car journeys in the UK which are under five miles. It has to be a real option for the quarter of all car journeys which are under one mile. No-one is saying everyone has to walk or cycle for all journeys, but the statistics show that they can work for many more than you may think.

The data is all well and good but the Midlands needs to invest heavily to make this change happen; many won’t cycle because it doesn’t feel safe. And this change needs to happen now. If we need any more convincing, for every £1 spent on cycling infrastructure, returns of £5.50 are delivered, according to the Department for Transport’s own figures.

Now, more than ever, the Midlands economy needs a rejuvenation not of mechanical engineering, but civil engineering, as we look for our city’s streets to adapt to the needs of 2020 and beyond. The response to COVID-19 has meant a noticeable policy shift to active travel, namely cycling and walking, as part of the national recovery effort. Just this week, £17.2m has been made available for rapid deployment of cycling and walking infrastructure in the West Midlands. We need to act now.

Motor cities like Birmingham have released ambitious emergency plans to repurpose street space for cycling and walking; this is on top of previously announced plans for so-called Ghentrification – the nickname given to Birmingham’s zonal traffic circulation plan, which took inspiration from the Belgian port city of Ghent, having successfully implemented their plan in 2017. The Motor city of Coventry will pilot e-scooters from as soon as June 2020 and the city has an ambitious light rail project in the works.

It’s not gone unnoticed that some cities once known for cars are doing quite a lot to undo the negative impact of our addiction to driving, especially for short journeys. Following Birmingham’s emergency transport plan, Conservative Cllr Meirion Jenkins wrote to the city council’s Labour leadership claiming that “it is quite wrong to use this period of national crisis to promote Labour’s anti car and anti motorist dogma. Birmingham is a motor trade city; many hardworking people rely upon the motor trade to make their living.”

In doing so, Cllr Jenkins is going against the narrative set by his party’s leader and Transport Secretary, Grant Shapps. But it’s easy to see why the car has an almost sacred existence here; 54,000 people are employed by the motor industry in the West Midlands, 2% of all employment in the area. These figures are significant and hard to ignore. But, it has to be clear now that we are not the motoring region we once were. While driving will always be part of our transport system, we can’t let it overrule the need for a more balanced and equitable transport system.

Innovations in transport in the Midlands have no doubt had a global impact on mobility. From bicycle manufacture and eventually the motorbike, car and aircraft industries, the Midlands has had a mighty impact on moving people. It shouldn’t be forgotten but increasingly, it’s known that mobility needs to work for everybody. In Coventry, for example, 33% of people don’t have access to a car; for a city famous for making cars, its residents have below-average car ownership.

Some people believe that the Midlands’ economic future will look like a newer, shinier version of its manufacturing past. There’s no doubting we have some of the best universities and companies ready for a future of electric and driverless vehicles. And that will be part of our future, but we need to be mindful that it doesn’t dominate as the car has before. Electric vehicles still cause congestion and share many of the same negative impacts on wider society as their combustion engined cousins. What’s more, they still produce pollution through tiny particular particulate matter air pollution. While the impact is not yet fully understood, early indications suggest PM2.5 can have an impact on a child’s brain development.

Instead of driverless cars, increasingly, many people believe we need more car-less drivers. In the same way the government pushed us to diesel cars, we’re about to embark on an electric car frenzy, without even knowing if it will be good for us. Let’s stop and think. It’s easy to forget the power of the bicycle, instead lured to shinier, more powerful inventions. But the enemy of the private motor car is more apparent than ever; space. It’s arguably the most valuable and finite resource in any city; space defines so much of how a city operates.

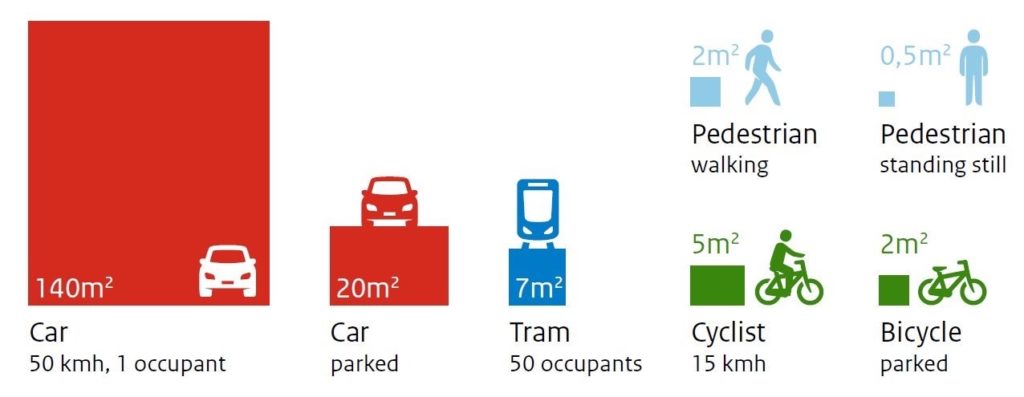

And when it comes to space, bikes are best. Up to seven times more bicycles can travel in a 3.5 metre lane than cars during the same time frame. According to the Netherland Institute for Transport Analysis, a cyclist moving at 15km/h requires 5m2 in a city, whereas a single occupancy car travelling at 50 km/h requires 140m2 of space.

In the glory years, the car was the ultimate in unhindered social mobility. But now there are so many of them, it’s gone too far the other way, with congestion costing the economy £7.9bn each year, not to mention the effect on our mental and physical health.

Some cycling advocates will try to remove the car from history, but for me, there is no doubt that cars have been a significant factor in social mobility; but this unhealthy overadoption is now what’s choking us. We have both environmental, congestion and inactivity crises that aren’t going to go away without drastic change.

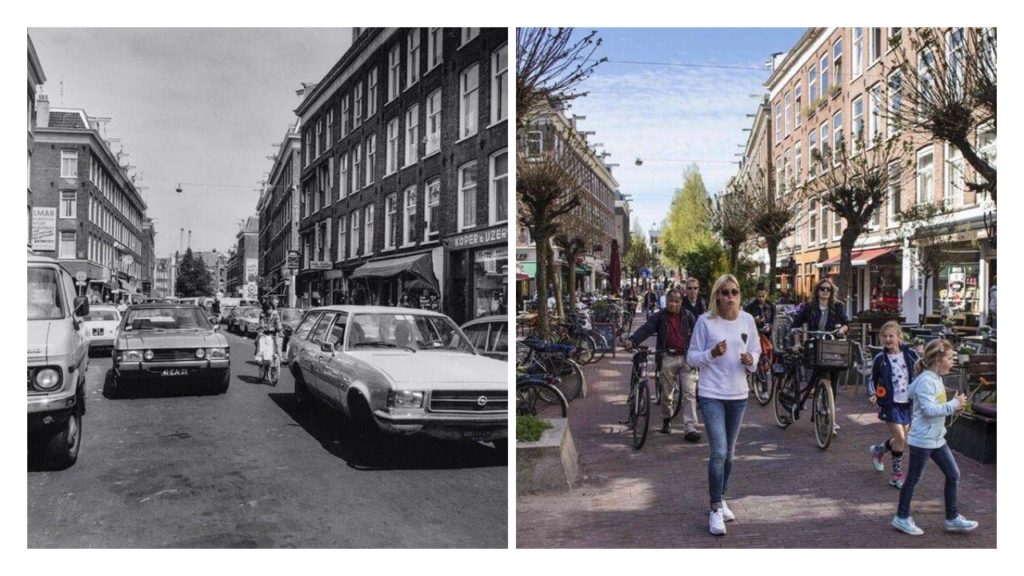

To understand where I feel the Midlands needs to go, you need to look at how other territories are using the innovations that the Midlands once gave them. Walk (or cycle) through the streets of any Dutch town or city and it’s impossible not to be amazed by the sheer number of people on bicycles. In fact, there are more bicycles than humans in Amsterdam. In the Netherlands as a whole, they have 32,000 km of cycle paths; in the city of Utrecht, 51% of journeys are made by bike, according to data from the Knowledge Institute for Mobility Policy.

Amsterdam has twice the number of trips cycled than taken by private car. While the Dutch are not immune to the lure of the private car; they own more cars per head than Brits, they don’t use them for short journeys. Thanks to Dutch government subsidies, electric cars are a popular sight, especially for road trips during the summer holiday season; lengthy queues of Teslas at toll booths are a frequent occurrence.

But the heart of the transport system in the Netherlands is the humble bicycle. And not just any bicycle. The most common form of bicycle design is the exported safety bicycle design from Coventry pioneer James Kemp Starley. Unlike us, the pioneers, the Dutch haven’t forgotten the power and efficiency of the bicycle we practically invented.

They’ve found a winning formula and it started in the 1970s. If we want a better and more equal future, we have to start now and work quickly. As urban planning expert Brian Deegan says, people pay a premium to visit Centre Parcs on holiday, dropping their car off on the outside of the village and doing all their journeys by bike or by foot. We like this and people are willing to pay extra for the experience. Indeed, even The Automobile Association are suggesting “park and cycle” schemes at the edge of cities to encourage people to complete their journeys in an efficient and environmentally-friendly way.

Think about it: nobody comes back from a trip to the Netherlands and says “I had a nice time, sure, but I wish there were more cars.” We know what good looks like, we just need to believe it’s achievable. Look at any pictures of the Netherlands in the 70s, and take a look now. Ask yourself: Which scene would I prefer to live in?

What sort of Midlands would you like to live, work and visit? One for people, or one for machines? It’s time to choose.

About Adam Tranter:

Adam is the Bicycle Mayor for Coventry, co-host of Streets Ahead podcast and CEO of communications agency, Fusion Media.

Connect with Adam on Twitter

Connect with Adam on LinkedIn