Each Autumn, the Government provides an annual rough sleeping snapshot, which gives an overview of the estimated number of people sleeping rough in England on a single night between 1 October and 30 November, as well as some basic demographics details (age, gender, nationality). The data, which is collated by outreach workers, local charities and community groups and is independently verified by Homeless Link, goes some way to identifying the trends in rough sleeping across different parts of the country.

In this article, Alan Fraser (a Member of our Housing and Communities Leadership Board and a Consultant with 30 years of experience working in housing and homelessness) provides an analysis of what the figures mean for the West Midlands and why a regional approach is essential to end homelessness.

Rough Sleeping is a regional problem, not a local one

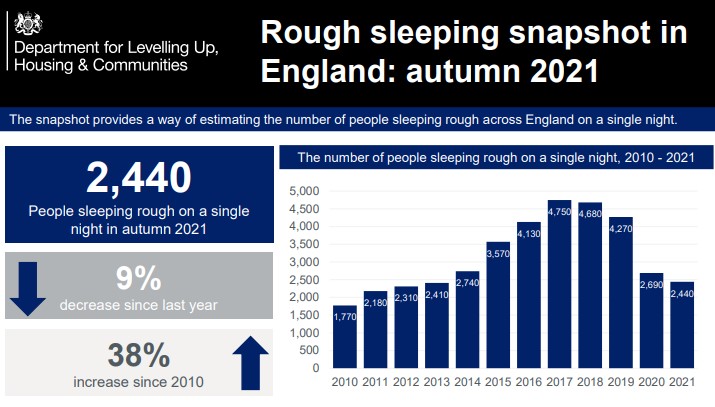

The government has released the latest figures for the number of people sleeping rough in England. Whilst measuring this cohort is notoriously tricky, there is a recognition that local authorities’ methodologies have improved over the years and that the government’s annual rough sleeping snapshot provides the best and most accurate picture that we can assemble of how many people are sleeping on England’s streets.

The good news is that nationally, we have seen further reductions in the numbers of rough sleepers across England. Having risen steadily since 2010, last year’s figures showed a dramatic 37% decline in the number of rough sleepers, largely because of the impact of the pandemic and the government’s ‘Everyone In’ strategy. There had been much commentary suggesting that with the easing of pandemic restrictions, and the consequent rolling back of funding for ‘Everyone In’ initiatives, that this year might see a bounce-back in those figures. But that has not happened. In 2021 there was a further 9% fall in rough sleeper numbers nationally – meaning there has been a nearly fifty per cent decline in rough sleeping since the peak in 2017.

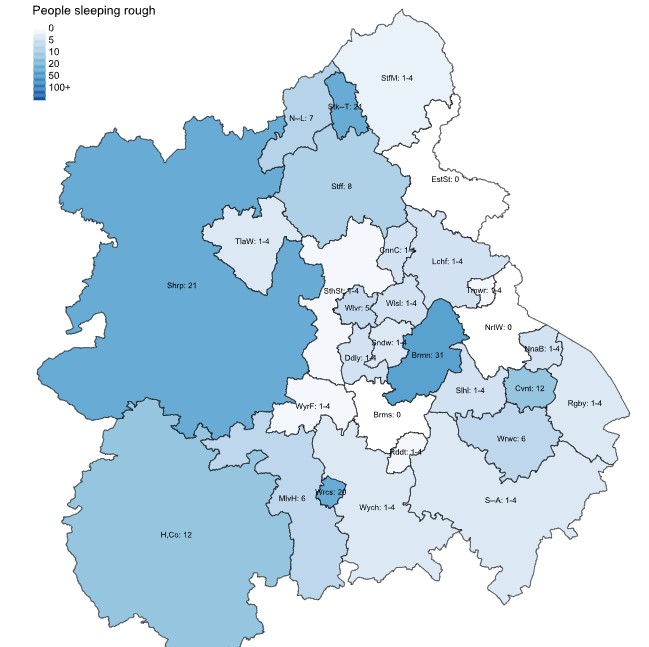

The further good news is that this decline has happened in every region of England – including here in the West Midlands. In 2021 there was a 10% fall in rough sleep numbers in the West Midlands (roughly in line with the national average) from 210 to 190. This is testament to local authorities’ strenuous efforts to try and embed the gains that the ‘Everyone In’ initiative brought.

But sadly, the report is not all good news. Birmingham bucked the national and regional trend and saw one of the largest increases in rough sleeping anywhere in the country – a whopping 82%. Now it must be said that this increase was from a very low base (there were just 17 rough sleepers recorded in the 2020 rough sleeper count) and follows on from a year in which Birmingham had one of the largest reductions in the number of rough sleepers. We should remember too, that the 2021 figure of 31 rough sleepers is still well below the peak of 91 that was recorded in 2018. But it is frustrating that the city has not been able to hold onto the impressive gains of recent years, and I think we’re entitled to ask why not, particularly in light of the significant investment that the West Midlands Combined Authority has made in an initiative called Housing First which was specifically designed to further reduce rough sleeping across the region.

There are lot of theories about why Birmingham’s numbers have increased, but from my own experience there are two issues which might help to explain Birmingham’s status as a rough sleeping anomaly.

Firstly, it may well relate to the city’s heavy reliance on so-called ‘exempt’ accommodation and changing attitudes towards risk from rough sleepers themselves. Historically, Birmingham was hit very hard by the government’s cuts to funding which helped support services to rough sleepers (the Supporting People programme). The Council’s response to the resultant crisis was to allow private landlords to pick up the slack. None of this was housing was regulated and so much of it was of poor quality and the management of it was often non-existent. In my time running a homeless organisation we came into contact with many people who had left this exempt accommodation because they felt unsafe there. For some people therefore, sleeping rough actually felt a safer option than staying in the housing that was on offer. When the pandemic hit, however, the risks of being alone on the streets with no shops open and no access to support services seemed too high. There was a concerted effort to identify and rehouse rough sleepers and funding available for councils to do it. Once that funding was cut back and the threat of the pandemic seemed to recede, the prospect of having to return to the exempt accommodation sector (where there are more than enough bedspaces available to house all of the recorded rough sleepers in the city) was obviously more than at least 31 people were prepared to face.

But is also the case that cities like Birmingham – regional hub cities – often attract a lot of people from other areas who end up sleeping rough. It is surely not a coincidence that local authorities neighbouring both Birmingham and Manchester have seen their rough sleeping rates continue to reduce whilst Birmingham has seen theirs increase and Manchester remains one of the country’s rough sleeping hotspots (with even higher numbers of rough sleepers than Birmingham). We have to recognise that large regional hubs like Birmingham aren’t simply dealing with their own rough sleeping problem; they are often dealing with rough sleepers from surrounding areas too.

When ‘Everyone In’ funding was wound down and the temporary accommodation that had been offered to rough sleepers in neighbouring local authority areas was withdrawn, people were drawn (and, in some cases, directed) to Birmingham. The notion that, as the regional hub, Birmingham has a wider range of housing options and more extensive homeless support services than other areas is surprisingly prevalent. In reality, there is an argument for saying that the reverse is true: Birmingham was harder hit by funding cuts than most other councils and therefore services are even more stretched.

This is where a regional solution might be helpful. If Birmingham is picking up more than its fair share of rough sleepers, then we should also be concentrating regional funding initiatives on the city so that homeless services can provide adequate support. But clearly, Birmingham doesn’t want to end up with a responsibility to permanently house a whole load of people from across the region. That is why in addition to delivering funding for rough sleeper support focussed on Birmingham, regional funding initiatives should concentrate on linking those services to permanent accommodation options across the region.

We need to think in a far more co-ordinated way about people’s pathways into and out of rough sleeping. Whilst it might be unreasonable to expect a largely rural local authority like Bromsgrove (for instance) to have a specialist accommodation unit for those with substance misuse problems, it should be far easier for people from Bromsgrove to access that accommodation in Birmingham where such a service – and a range of other support services – could be provided far more cost effectively. But it also needs to be far easier for that service in Birmingham to liaise with housing options workers in Bromsgrove when the person has been treated and is ready to look for permanent accommodation. Too often people end up stranded between temporary accommodation in places where they have no connection, and a lack of the necessary support to enable them to sustain a tenancy in the area where they are from. Rather than thinking in terms of which individual local authority is responsible for an individual rough sleeper we have to deliver the most robust, professional rough sleeper services that we can in the places where the rough sleepers gravitate to, and then look to connect them into the places where they want to be. This means breaking out of local authority thinking, and beginning to think regionally.

Alan Fraser has worked for nearly thirty years in the fields of social housing and homelessness, all of it in the West Midlands. He has worked for a charity, a large housing association, a local authority, and a stock transfer housing association before becoming a chief executive within the YMCA federation. He now works as an independent housing consultant and is a Member of the Housing and Communities Leadership Board at the Centre for the New Midlands.